Representation of the constellations

The features of celestial globes reveal the aspirations of their builders, who either decide to follow conventional iconographic representations of the constellations or to create new ones instead.

Mercator distanced himself in a number of ways from his master Gemma Frisius. For experts such as Elly Dekker (1994), he apparently tried to reconcile the opinions of Claudius Ptolemy and Nicolaus Copernicus.

For example, in the 16th century, the constellation Lyra was traditionally shown as a bird or as a combination of a bird and a sort of violin. These representations stem from the Arab influence in the circulation of Ptolemy’s Almageste. Seeking greater accuracy, Mercator replaced the bird-violin image with a Vultur cadens, a musical instrument of Greek origin that was unknown in the Arab world. The Greek version of the Almageste actually described Lyra as being composed of a “shell” (i.e. a tortoise shell, like the one used by Hermes to make the very first lyre) with horns and a crossbar.

- Lyra (Pierre Apian, Caesareum Astronomicum, 1540)

- Lyra (Gerardus Mercator, celestial globe, 1551)

- Lyra (Johannes Hevelius, Uranographia, 1690)

A number of human figures are dressed on Mercator’s globe whereas Frisius shows them naked.

- Orion (Orion)

- Bubulcus (Bouvier)

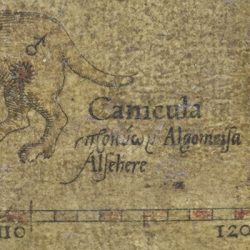

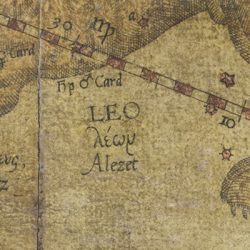

Mercator’s cartographic aspirations can also be seen in the sizeable nomenclature of individual constellations and stars. The constellations are identified by their Latin and Greek names with a transliteration in Arabic (or what is meant to be Arabic). Such efforts point up Mercator’s erudition. From this point of view his celestial globe is the most comprehensive of any made in the 16th century. Here are a few of Mercator’s additions :

- Ceginus (Gamma Bootis, Phi Bootis),

- Incalurus (Mu Bootis),

- Saclateni (Êta Aurigae),

- Angetenar (Tau Eridani),

- Acarmar (Thêta Eridani),

- Alphart (Alpha Hydrae),

- Markeb (Kappa Puppis, Kappa Velorum)

- etc.

- Canicula (Dog Star, Sirius)

- Capricornus (Capricorn)

- Leo (Lion)

Find out more

- Constellations : in his representation and of the constellations and his nomenclature, Mercator produced the most comprehensive celestial globe of the 16th century.

- Dekker, E., Krogt, P. van der (1994) pp. 260-263.