Printed globes

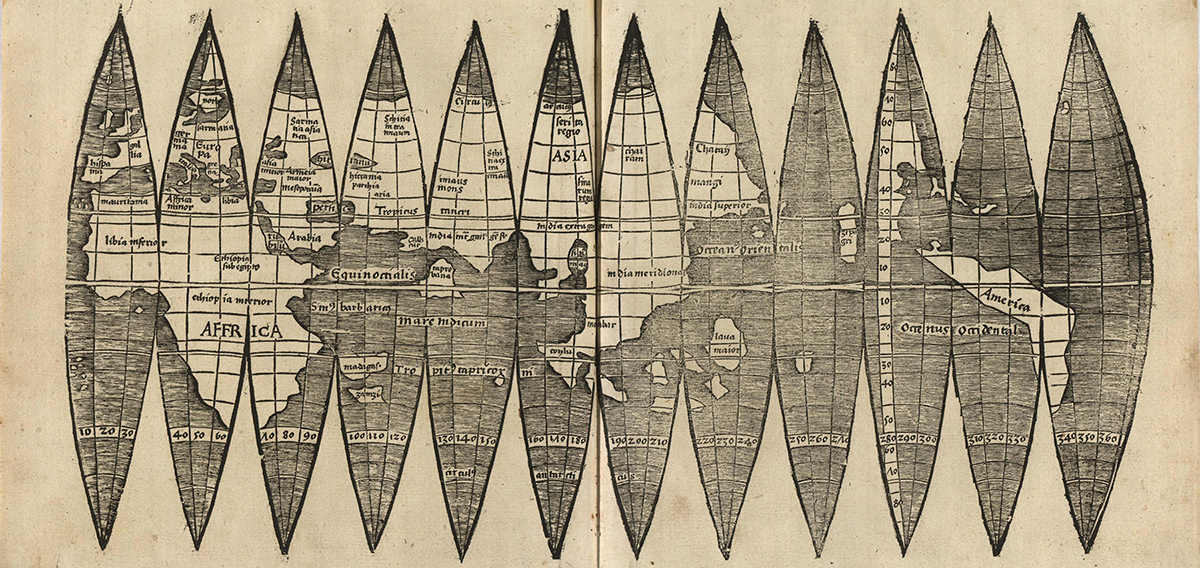

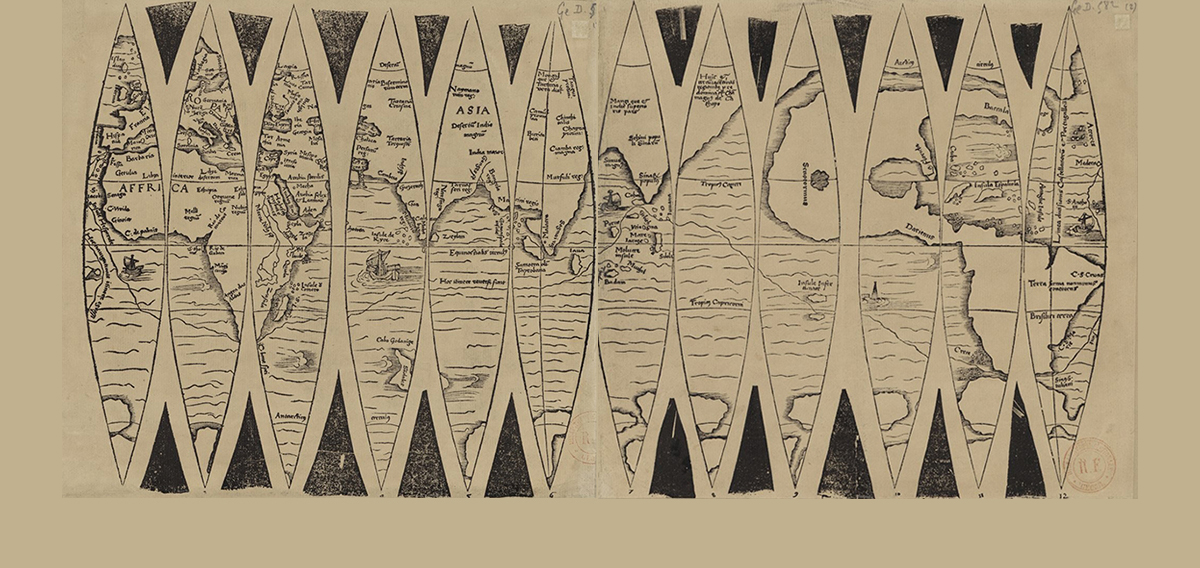

Initially globes were solid spheres made by hand from a variety of materials such as marble, glass, wood or metal. Later they became hollow spheres consisting of thin sheets of metal including copper. Obviously, these were single copies. The advent of the printing press in the mid-15th century made it possible to produce globes more cheaply in limited series. In this case they were made starting from wood or copper engravings printed on paper gores, which was then cut out and pasted onto the sphere.

The assembly of a printed globe began by making a hollow sphere separated into two hemispheres composed of cellulosic material such as papier mâché or cloth pasted in successive layers. The two hemispheres were joined and mounted on a central shaft, allowing the sphere to rotate. However, because the weight was seldom evenly distributed, globes were usually out of kilter. To balance them on their axis, little pockets of copper or sand were sometimes placed inside, thus preventing them from sagging in a particular spot. The printed gores were then cut out and pasted on the sphere. Such globes were fragile and difficult to transport.

In the 16th century, Flanders and the Low Countries became important intellectual and scientific centres where intaglio printing flourished. Thus, all the ingredients were combined for Gerardus Mercator to be able to produce top-quality printed globes. Though destined for the upper classes, these gradually made it possible to disseminate knowledge to a wider public.

From 1500 to 1830 printed globes were always produced and exhibited in matched pairs, one celestial and the other terrestrial. Together they symbolised the universe of knowledge and knowledge of the Universe. By portraying the Earth and the Cosmos as identical size, they moreover conveyed a different relationship in which the Earth became an object in itself, capable of being thought about independently, no longer subordinated to the heavens above. Nor did this vision encompass only the oecumene (inhabited land) and instead provided a broader geographical perspective. From 1830 terrestrial globes little by little developed a solo career whereas celestial globes were increasingly regarded as curios and fell by the wayside before finally being replaced by the modern-day planetarium.

So printed globes, produced and distributed quickly in series of varying size, became the standard. Surprisingly, the methods used to craft them, set out very clearly by Gerardus Mercator, have barely changed since the mid-16th century.

Find out more

- Bellerby & Co. Globemakers : a modern-day workshop for making craft globes