The beginnings of terrestrial cartography

Human awareness of time and space arose in the distant past, before the dawn of history. The sun, the moon and the stars, serving as both clock and calendar, gradually provided points of reference for travelling, sailing and planting crops. Historically, celestial representations preceded terrestrial ones. Modern societies’ idea of making models of the Cosmos and the Earth based on the laws of geometry was, to a large extent, a legacy of the ancient Greeks.

- Thales of Millet (c. 625-547 av. J.-C.)

- Anaximander of Millet (c. 610-546 av. J.-C.)

- Eudoxus of Cnidus (c. 408-355 av. J.-C.)

- Eratosthenes of Cyrene (c. 276-194 av. J.-C.)

- Ptolemy of Alexandria (c. 90-168 ap. J.-C.)

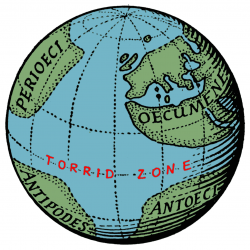

From the 4th century BC the ancient Greeks represented the celestial vault as a sphere. References can also be found to terrestrial globes made, for example, by Eudoxus of Cnidus (c. 276-194 BC) and Crates of Mallus (c. 220-140 BC). The image of the Cosmos changed little after Antiquity, but for the image of the Earth it would be a different story.

In ancient Greece it was writings that mattered. Those of Hesiod (8th century BC) and Homer (8th century BC?), with the Iliad and the Odyssey, are indicative of that mythical time when the world was a narrative ensemble.

The classical Greek period gave rise to measurement. Geometry developed gradually. Thales of Millet (c. 625-547 BC) envisaged the Earth as a sphere and Anaximander of Millet (c. 610-546 BC) revealed for the first time that the Earth was a heavenly body.

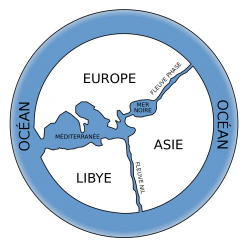

Finally, during the Greco-Roman period, pragmatism and science gained the upper hand. The Earth became a territory. Eratosthenes of Cyrene (c. 276-194 BC) was the first to measure its circumference while Ptolemy of Alexandria (c. 90-168) would sum up this store of Greek knowledge in the 2nd century AD. The advance of cartography in the 16th century owed much to ancient scientific works via their translation into Latin and availability in print, particularly the works of Ptolemy. His Geographia, a roundup of the knowledge of world geography inspired by Marinos of Tyre, was published with maps for the first time around 1477. The Almagest, his monumental work on astronomy, imposed a geometric vision that would long be regarded as the standard model of the universe, until the idea of a heliocentric view was proposed.

Find out more

- Ptolemy’s contribution : it could be said that the Greek scientist Ptolemy was at once the last of the great cartographers and astronomers of ancient Greece and the first in the Western world.