The beginnings of celestial cartography

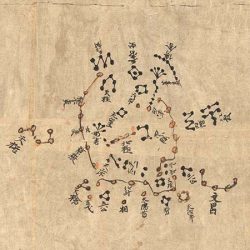

While the oldest surviving celestial map was drawn by Dunhuang (649-684) in China, we must refer to Greek science to retrace Western history’s spherical representations of the heavens.

- The map by Dunhuang (649-684), a full celestial atlas, was found in a Buddhist monastery on the Silk Road in China. It is drawn on a thin paper scroll 394 by 25 cm.

- The Farnese Atlas is a 2nd-century AD marble, no doubt a Roman copy of the original Greek one dating from the 3rd century BC. That would make it one of the oldest known celestial globes. It shows 41 constellations catalogued by classical science at the time of Eudoxus of Cnidus (c. 408-355 BC) and Hipparchus of Nicaea (c. 190-120 BC). They are represented as inverted images in the classical style.

- This imaginary portrait of Ptolemy, depicted as he appeared in the first printed books, shows the scientist with a quadrant and accompanied by a personification of astronomy. His crown stems from a mistake made frequently in the Middle Ages, namely that he was one of the Ptolemaic kings of Egypt (Gregor Reisch Margarita Philosophic. Strasbourg, 1504).

Using a globe to model the geometry of the heavens was essential to Greek astronomy, where this spherical representation took hold from the 4th century BC. Most of these globes depicted the constellations in allegorical form with their main stars and a number of circles such as the meridians, the equator and the ecliptic.

In his Syntaxis mathematica, better known by the title Almagest, Ptolemy (2nd century AD) analysed the various components of the Earth-Heavens system geometrically. He also discussed the construction of celestial globes, listing 48 constellations, the ecliptic coordinates of 1022 stars and their size (which he called “magnitude”). With few improvements this breakdown of the heavens held sway for many centuries, including into the 1500s.

Arab science preserved the fundamentals of Greek astronomy from 900 to 1300 AD. The knowledge of stereoscopic projection, used in astrolabes, was thus handed down to the Western Latin world around the year 1000 via Muslim Spain. A dozen celestial globes, made of brass and produced in the Arab world during the Middle Ages, are currently known to exist.

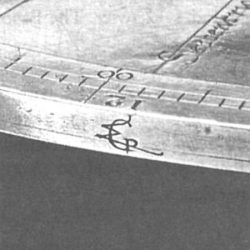

- Astrolabe by al-Shali, Hijri year 459 (Toledo, 1067).

- Historians recently discovered three astrolabes believed to have been made by Gerardus Mercator. One is conserved in Florence, one in Augsburg and one in Brno. Here we see the Augsburg astrolabe dated in the 1570s.

- Mercator’s monograph on the Florence astrolabe. This illustration is from the article by Gérard L’E. Turner (2005).

In the Christian world, representing the vault of heaven on a globe became a popular way of telling time. This was mainly useful for planning religious celebrations including Easter. Small wonder then that the first celestial globes in western Europe were to be found in monasteries. They are extremely rare, however, as they were single copies carved out of wood.

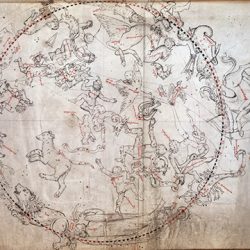

One of the first celestial maps in the Western world was the Vienna Manuscript, an anonymous work produced around 1440 and currently conserved by the Austrian National Library. This map represented an important step in the development of mathematical cartography in Europe. For the first time, the human figures embodying constellations are drawn from the back.

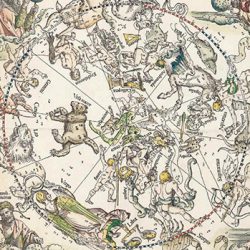

Representations of the Cosmos emerged in earnest during the Renaissance. Scientists in this period began to demystify the heavens by breaking away from medieval mythologies and establishing a new tradition based on mathematics. Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Conrad Heinfogel († 1517) and Johann Stabius (c. 1460-1522) produced the first printed star maps, no doubt inspired by the Vienna Manuscript.

- Boreal planisphere in the Vienna Manuscript (MS 5415 fol. 168 r.)

- Albrecht Dürer was the author of a geometry for painters and was in touch with German geographers. He took part in a study on Ptolemy and is credited with the production of two celestial planispheres and a map of the world. His work illustrates the close relationship between cosmography and the development of perspective (Imagines coeli Meridionalis, Albrecht Dürer, 1515).

- Mainly famous for its anamorphosis, The Ambassadors, painted in 1533 by Hans Holbein the Younger, depicts a number of humanist subjects typical of the Renaissance including a celestial globe that could be the one by Johann Schöner.

These maps were followed in 1515 by the first printed celestial globe. Made in Nuremberg by Johann Schöner, it was 27 cm in diameter and covered with gores printed from wood engravings. This globe, part of a matched pair with the terrestrial one, seems to have served as a model for the one in The Ambassadors, a 1533 painting by Holbein the Younger.

In 1537 the mathematician, astronomer, physician and geographer Gemma Frisius produced a globe in Leuven, this time using copper plates, which represented a significant step forward in globemaking. Frisius referred to himself on his work as a medicus ac mathematicus, a designation explaining how it integrated medicine and astrology, two fields that were then linked by a macrocosmic and microcosmic vision of the elements and the “humours”.

- One of the two known copies of Johann Schöner‘s celestial globe (c. 1534)

- Only one copy of Gemma Frisius’ celestial globe survives today, conserved at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

While drawing on Dürer’s work, Frisius improved the representation of the Cosmos by adding numerous details: the tip of Eridanus was probably inspired by the German mathematician Peter Apian (1495-1552); the precession of the equinoxes (19°40’) was identical to Dürer’s; the magnitudes of stars were better designated; and a number of star names were added. The globe also featured references to astrological relationships between stars and planets, for example by associating Venus and Mercury with Spica or Saturn and Mars with Aires.

In 1551 Mercator followed the example of his master Frisius and matched his own terrestrial globe with a celestial one 41 cm in diameter. The pair marked a major milestone and, establishing Mercator as the father of modern globemaking.

Find out more

- Bonnet-Bidaud, J.M., Praderie, F. & Whitfield, S. (2009) « The Dunhuang chinese sky : a comprehensive study of the oldest known star atlas », Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, Vol. 12, N° 1, pp. 39-59.

- Dekker, E. (2013) Illustrating the phaenomena : celestial cartography in Antiquity and the Middle Ages, Oxford : Oxford University Press.

- Whitfield, P. (1995) The Mapping of the Heavens, London : The British Library.