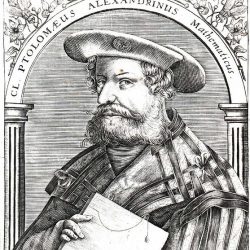

Ptolemy’s contribution

The astronomer and geographer Claudius Ptolemy (c. 90-168) spent his life in Alexandria, the main centre of scientific learning of the time. One could say that he was at once the last great cartographer and astronomer of Antiquity and the first of the Western world. A master compiler, he owes much of his reputation to the fact that nearly all his work was conserved by Arab scholars and then translated into Latin.

His most famous work is a treatise on astronomy divided into thirteen books known by the title Almageste. In it Ptolemy professed a geometric conception inherited from Hipparchus (c. 190-120 BC), which placed the Earth as a sphere at the centre of the universe. This conception would leave astronomy at a standstill until the advent of observational instruments and the proposal of a heliocentric system by Copernicus (1543), Galileo (1630) and Kepler. The Almageste also contained a catalogue of 1022 stars and 48 constellations that Mercator would use for his celestial globe.

- Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543)

- Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)

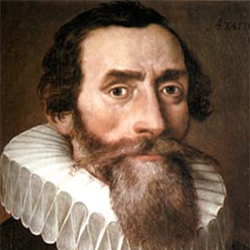

- Johannes Kepler (1571-1630)

Ptolemy’s second work, Geography, was concerned with describing the Earth. It is not known whether it was an original treatise or a vulgarisation. In it Ptolemy explained that geography had to faithfully project the reality of the physical world using maps. The work was also a sort of cartographic glossary of known places and their locations.

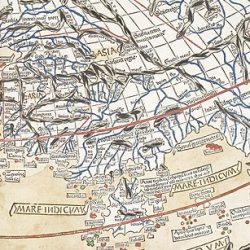

The first printed copy of Ptolemy’s Geography containing maps, published in 1477, summarised the state of geographical knowledge around the year 125. For Renaissance scientists it provided an introduction to mathematical cartography, to the use of cartographic projections, to latitudes and longitudes as a grid for maps’ content and to new factual knowledge about geography. The work contained a very famous map of the world easily suggesting that by sailing towards the west one could reach the Orient. This representation was reproduced with its errors until the 17th century.

Ptolemy’s works were both a fillip and a muddle for cartography as a science. By depicting the Earth as a sphere, they sparked a search for a way to project this spherical shape onto a plane. By pointing up the need to determine the locations of places in relation to the equator and a prime meridian, they would provide an impetus to mapmakers. But by passing down the imprecisions of geography as it stood at the end of Antiquity into maritime mapmaking, a field that although still empirical was nevertheless much closer to reality, Ptolemy’s conception obscured the truth.

Find out more

- Ptolemy’s Geography : 1478 edition with engravings by Konrad Sweynheim and Arnold Buckinck, made available in digitised format by the World Digital Library.