America

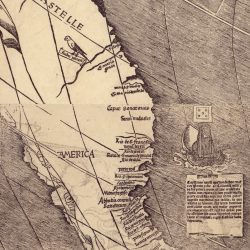

- Waldseemüller’s America

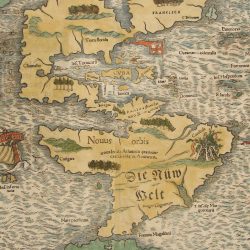

- Munster’s America

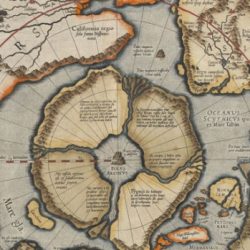

- Mercator’s America

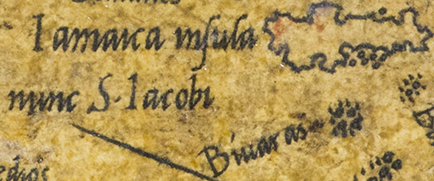

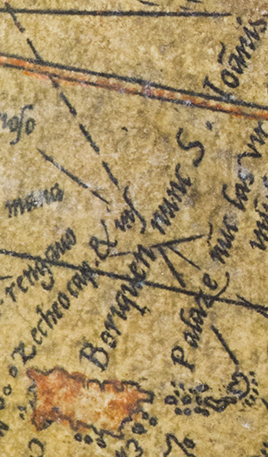

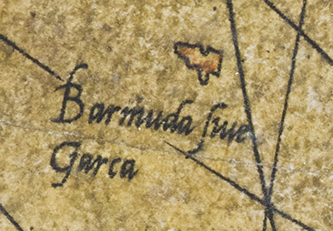

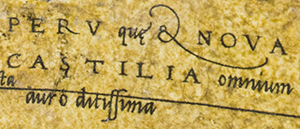

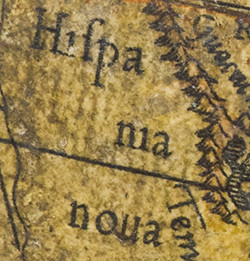

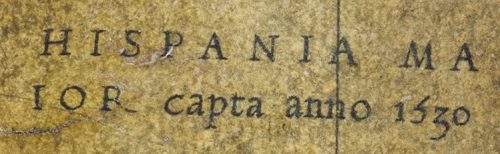

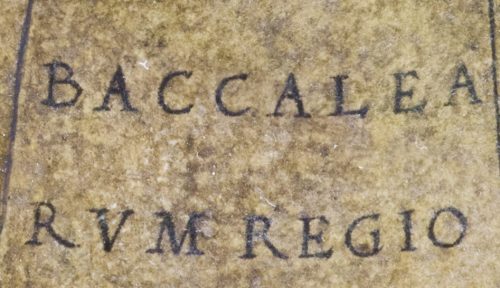

Mercator’s America is a largely unexplored continent whose outline are still uncertain. The western shorelines of North America and the southern shores of South America appear uncharted, with no place names, contrasting sharply with the rich toponymy of the eastern coastlines, the Caribbean and Central America. These were already well documented by the great contemporary discoveries.

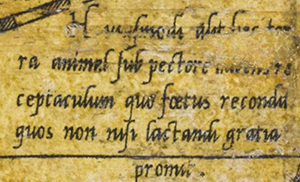

South America is shown wider than its actual east-west dimension and too short north-south. To fill part of the vacant space in the interior, Mercator drew an opossum, an animal that symbolised the tropics. Yet this image, inspired by other maps, is neither properly proportioned nor very realistic: here the opossum’s pouch sits at shoulder level, not at its hips.

While the shape and position of the Americas are incorrect, one wonders how Mercator was able to convey such a complete and fair image of continents that were still largely unexplored. His representation is innovative and almost faithful to reality compared with the misshapen attempt by a contemporary cosmographer, Sebastian Munster. Even maps published a century later in Holland would not be as precise.

Despite the Spanish and Portuguese courts’ censorship of details about their maritime expeditions, and despite the absence of newspapers, Mercator managed to glean an incredible amount of information. It was almost as if, map in hand, he had followed the mariners on their voyages of discovery and published the findings at the same time they were made known to the monarchs who had commissioned the expeditions.

- No way through

- North-West Passage

By Mercator’s day, explorers had already been seeking a passage over North America to the Pacific Ocean for some time. On the face of it the German-Flemish cartographer changed his mind about its existence sometime during his career. On his 1541 globe, the landmass continues with no break between North America and the Arctic. But on the map published the year after he died, in 1595, he drew a strait separating California and the North Pole.

While Mercator did not give the North-West Passage a name, the Spaniards called it the “Strait of Anian”. Several expeditions were already mounted to search for it throughout the 1700s. But despite the many attempts to find it over the centuries, the route would not be mapped out at last until 1906 by Roald Amundsen.

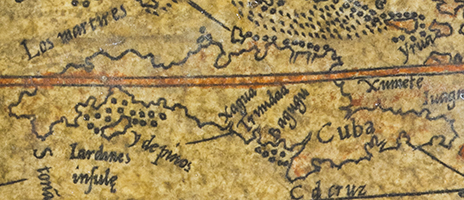

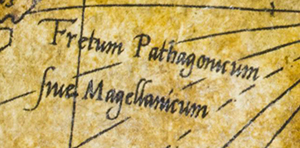

- Strait of Magellan

Christened Tierra del Fuego, the region seemed to spell bad luck for succeeding expeditions that would venture through it. Tierra del Fuego long remained an enigma and the cartographer Johann Schöner believed that another huge landmass lay south of the strait. The myth of this southern continent, conceived by the Greeks in Antiquity and handed down by medieval scholars, continued to be represented in the 16th century, for example on Oronce Fine‘s 1531 world map and on Mercator’s 1541 terrestrial globe.

It would not be until the 1580s that an expedition disembarked on the desolate shores of Tierra del Fuego.

Find out more

- Cosmographiae universalis : by Sebastian Munster, digitised document, National Library of Portugal

- Nova et integra universi orbis descriptio : by Oronce Fine, digitised document, National Library of France: Gallica